The matrons of the lodges […] have only to interpose their authority to turn aside all the best devised plans.

Father Jean-François Lafitau (1724, 101)

On October 27, 2022, at the Quebec Superior Court, the Kanien’kehá:ka Kahnistensera (Mohawk Mothers) obtained the first injunction ever granted to unrepresented Indigenous plaintiffs in Canada1 (Kahentinetha 2022). In response to the Kahnistensera’s request to search the grounds of the former Royal Victoria Hospital, in Montreal, for the unmarked graves of Indigenous children victims of the infamous MK-Ultra program2 in the 1950’s and 1960’s, Justice Gregory Moore ordered the defendants, McGill University and the Société québécoise des infrastructures (SQI), to halt excavation work for a redevelopment project seeking to transform the hospital into a new campus, and to negotiate the parameters of an Indigenous-led archaeological plan with the Kahnistensera.

This landmark decision was in the wake of the detection by Ground Penetrating Radar of approximately 215 potential unmarked burials near the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, in May 2021. Since then, searches in other residential schools across Canada located evidence of more than 2 300 unmarked burials as of June 2023 (Wyton 2023) – with hundreds of residential schools yet to be searched, not to mention reformatories, hospitals, sanatoriums, correctional homes, and mental institutions. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had officially characterized the events as a “cultural genocide.” However, the discovery of unmarked burials compelled Prime Minister Trudeau to acknowledge that “what happened was akin to genocide,” plain and simple (Alhmidi 2021), an assessment later affirmed by Pope Francis 1st during his visit to Canada in July 2022 (Deer 2022). At a press conference that the Kahnistensera held when the Pope was in the country, Mohawk Mother Kahentinetha said that the term “reconciliation” rings hollow in her language, which contains no words of apology (Tomesco 2022).

This article examines how such discrepancies between Kanien’kehá:ka and Western conceptions of responsibility and autonomy played out in the Mohawk Mothers’ court proceedings. Whereas in accordance with the Mohawk Mothers’ wishes I refrain from direct analyzing the inner workings of their councils, my reflection focuses on the significance of their refusal to use lawyers to represent them, exposing how Canadian courts tend to force their reappropriation of practices and the translation of terms and practices that have no equivalent in Indigenous cultures.3 Such disparities are probed using both court records and participant observation with the Mohawk Mothers and Kanien’kehá:ka knowledge keepers in 2022–2023. In addition to analyses based on the Teiohá:te (Two Row Wampum), the traditional Kanien’kehá:ka ethical framework for maintaining good relationships with foreigners, the conceptual identification between councils, families, and fires – encompassed by the word Kahwá:tsire’ – is invoked to highlight how Kanien’kehá:ka collective decision-making protocols respect individual autonomy.

Background and Underground

Growing up as a francophone in Montreal my knowledge of the neighboring Kanien’kehá:ka territories of Kahnawá:ke and Kanehsatà:ke, respectfully on the south and north shore of Montreal, was limited to the shocking images of the 1990 “Oka Crisis,” a 78-day standoff between Mohawk warriors and Canadian Armed Forces sparked by a conflict over the expansion of a golf course over an ancestral cemetery. Even though tensions with settlers were aggravated as news outlets regularly portrayed Mohawk Warriors as armed criminals threatening law and order, the Oka Crisis resulted in the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples being launched in 1991 to avoid future confrontations, eventually leading to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report in 2015. The same year, I met elders Tekarontakeh, Kanasaraken, and Ateronhiatakon, known for pioneering the revival of Indigenous militancy through the Mohawk Warrior Society in the 1960’s, as well as for their knowledge of the “old words” used in longhouse ceremonies, which brought them to travel throughout Rotinonhsión:ni4 (Iroquois) territory to conduct funerals and baby-naming ceremonies as much as political gatherings. Resisting, in continuity with their own ancestors, colonial and Christian acculturation5, they reject the usual translation of their ancestral constitution, the Kaianerehkó:wa, as the “Great Law of Peace,” in favor of the ecologically grounded and more etymologically sound term “Great Good Path” (Karoniaktajeh 2022, 261), referring to the path of a self-generated “Creation,” without need for any godlike “Creator.” For them the Rotinonhsión:ni could not have such a thing as “law” for the simple reason that they are a “free” people – as reflected in the word Tewatatewenní:io, “We all carry ourselves.6”

When I integrated into the anthropology department at McGill in 2020, everyone was aware of the Kanien’kehá:ka’s strong claim on the university, whose campus is situated on unceded land likely containing the archaeological remnants of the large precolonial village which French explorer Jacques Cartier witnessed in 1535. In addition to the Dawson site nearby (the largest archaeological site on the island of Montreal), construction workers accidently stumbled on a longhouse containing numerous burials and artifacts while excavating the road in front of McGill’s gates (Yakub 2018). In 2015, Kahentinetha, a Kanien’kehá:ka author and matriarch, sent a notice of seizure to McGill University on behalf of the Kanien’kehá:ka women, the titleholders of their traditional territory (Milum 2015).

The women’s duty to caretake the land was stipulated in Seneca anthropologist Arthur C. Parker’s (1916, 42) first published version of the Kaianerehkó:wa (“Great Good Path”): “The lineal descent of the people of the Five Nations shall run in the female line. Women shall be considered the progenitors of the Nation. They shall own the land and the soil. Men and women shall follow the status of the mother.” As explained by elder Tekarontakeh, Kanien’kehá:ka women do not directly “own” the land, but rather caretake it as a trust for its true owners, the Tahatikonhsontóntie, “the future generations still within Mother Earth’s womb” (Blouin 2022). Women have a tremendous power and responsibility in Rotinonhsión:ni (Iroquois) matrilineal society, both selecting and deposing male chiefs, with the help of the warriors, if they stray away from their responsibilities.7 The notice of seizure that Kahentinetha sent to McGill University reminded Canadians that the power and responsibility of Kanien’kehá:ka matriarchs goes beyond Rotinonhsión:ni peoples to include settler colonial encroachments onto the land and soils within their traditional purview.

Kahentientha’s intervention sparked discussions at McGill, and soon the university began organizing pow-wows and raising the Rotinonhsión:ni Confederacy’s flag above the campus for one week annually (McGill Provost’s Task Force on Indigenous Studies and Indigenous Education 2017). Yet the terms of the notice of seizure remained unaddressed and they would reemerge in court in 2022, once it became clear that the allegations of unmarked burials on the Royal Victoria Hospital site would not be acted upon. In the meantime, I had spent six years working on a book with founding members of the Mohawk Warrior Society (Karoniaktajeh 2023), with the intention of correcting the erasure and distortion of their tradition resulting from the bad press following the 1990 Oka Crisis. I gradually understood, however, that their erasure had deeper roots.

On the one hand, resistance to assimilation implied going underground at a time where precolonial Indigenous traditions were outright outlawed by colonial powers. In fact, the Kaianerehkó:wa (“Great Good Path”) explicitly states that, “should a great calamity threaten the generations rising and living of the Five Nations”, the Rotinonhsión:ni (Iroquois) should retreat and hide “beneath the Tree of the Great Long Leaves” (Parker 1916, 48). On the other hand, the absence of written evidence of their ways resulting from this retreat was often framed as evidence of an absence within the anthropological and legal record, while the few written traces that did appear were often dismissed as hearsay or outright politically motivated inventions. Although this situation is gradually being remedied by the hard work of Rotinonhsión:ni scholars Kahente Horn Miller, Kevin J. White, Theresa McCarthy, Susan Hill, Audra Simpson, and many others, for much of the 20th century the possibility that core elements of precolonial Rotinonhsión:ni culture could have endured centuries of forced assimilation was consistently questioned by non-Indigenous anthropologists. While the Kaianerehkó:wa (“Great Good Path”) itself was famously dismissed as a “figment,” that “does not exist […] either written or unwritten” (Parker 1918, 123), similar doubts were expressed over the authenticity of what became the main focus of my PhD research, the Teiohá:te (Two Row Wampum).8

Two Rows and One Circle

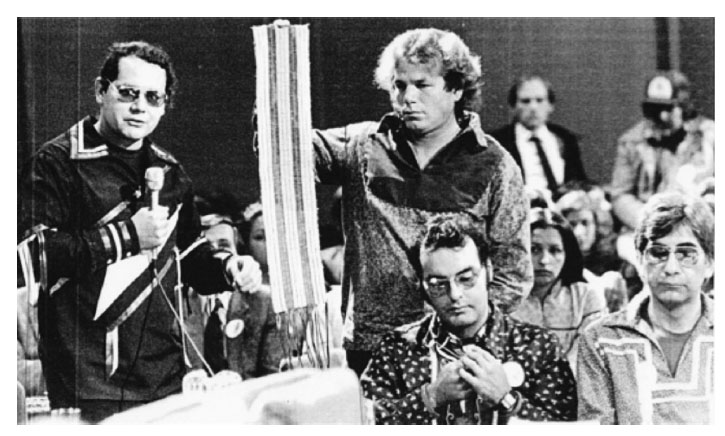

Despite these allegations, all the knowledge holders I consulted are adamant that they inherited their understanding of the Teiohá:te (Two Row Wampum) directly from their elders, who themselves received it from their own elders, and consider this wampum to be the original agreement passed between their ancestors and European settlers. The white and purple shell beads display two parallel lines, symbolizing two paths on a river, one for the settlers’ ship and the other, for the Indigenous peoples’ canoe (Fig. 1). The two rows indicate that both parties can only move in the same direction as allies if they remain parallel and separate, not deviating from their path. As I came to understand from discussing the Teiohá:te with elders, its allegory goes beyond the relationship with settlers, also defining the respect for difference in relations between Indigenous peoples, clans, age groups, genders, and even non-human beings. It was explained to me as the ethical principle underlying “all relations” (akwé:kon tetewatátenonhkwe, “We are all related,”) pervading the sundry complex and balances provided by the Kaianerehkó:wa (“Great Good Path”).

Figure 1: Teiohá:te held by Tekarontakeh at the National Assembly in Quebec City, 1983. Courtesy of Tekarontakeh.

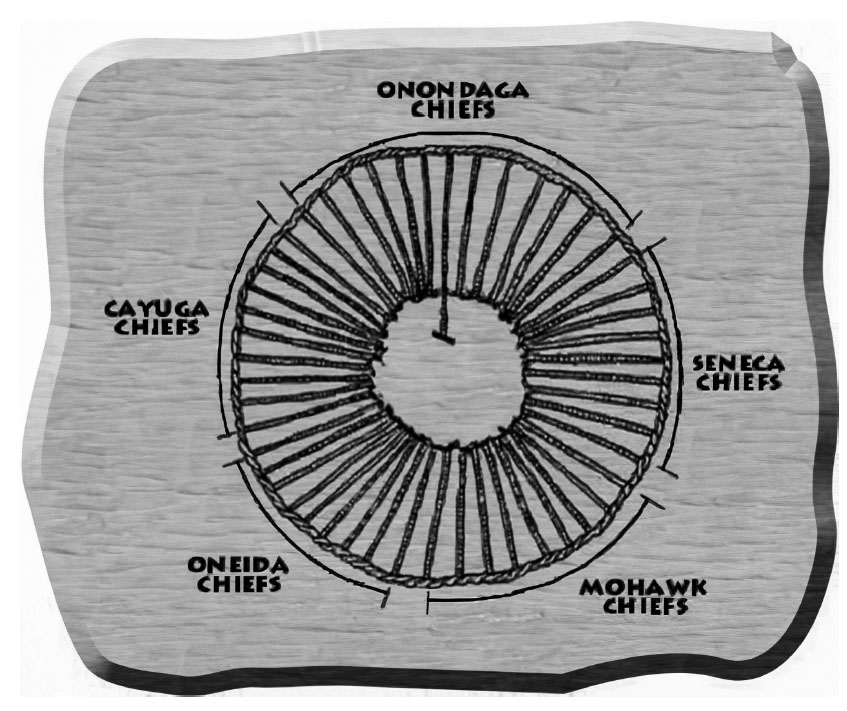

Although few historians, with the exception of Parmenter (2013), recognized the relationship between the Teiohá:te’s naval imagery and the “Silver Covenant Chain,” the diplomatic framework historically linking the Rotinonhsión:ni with the British crown,9 Tekarontakeh explains that the Europeans’ ship was originally allowed to dock to the continent of A’nowarà:ke, (“Turtle Island10”) (Tekarontakeh 2021). Settlers were given the right to the depth of a plough for their subsistence, but their ship had to stay in the waters, at bay, as Turtle Island was not their “motherland.” Europeans were said to “have no path” – iah tehotiianerenhserá:ien – inside the continent. The word “Canadian,” Kanatién, which some translate as “they embedded themselves in the village,” or more literally “squatters” (Kahentinetha 2019), indicates how settlers renegaded the Teiohá:te’s commitment to stay at bay by embedding colonial infrastructures deeper than the depth of the plough,11 as policies of assimilation on the one hand, and of cultural appropriation on the other, “double crossed” its agreement to maintaining parallel paths. Several traditional Rotinonhsión:ni people explained to me that the wood-cladded courtroom embodies the cockpit of the settlers’ ship which embedded on Turtle Island the extralegal “admiralty law” of the seas inherited from Pope Alexandre VI’s 1493 Inter Caetera bull, which resulted in all lands west of the Atlantic being deemed an extension of the Ocean, a terra nullius.12 Following this logic, traditionalists explained to me that Indigenous litigants should never cross the physical space of the bar (rudder) in court to avoid being subjected to this admiralty law. According to Kanenhariyo (Real Peoples Media 2020), the Two Row Wampum only allows to board the settlers’ ship to warn them that troubled waters are ahead, and correct its course. On his part, Karoniaktajeh (2023, 157) states that the Kaianerehkó:wa does not admit dual citizenship; if someone leaves the native canoe and exits the circle of families, Teiotiohkwahnhákton (Fig. 2), to follow another law, such as Canadian law, they will have to wait a whole generation on the edge of the circle before entering it again.

Figure 2: Teiotiohkwahnhákton, Circle Wampum, protecting the forty-nine Rotinonhsión:ni families. Courtesy of Mohawk Nation News.

In the following pages I will examine how, by refusing to be represented by an attorney, the Mohawk Mothers sought to “present”– rather than represent – their existence and concerns within the settler’s ship while remaining within their own row, as a distinct people – albeit not as foreigners, but rather as emerging from the underground of Canada, preceding it from time immemorial. By refusing to be represented, they could present themselves in a Canadian courthouse without subjecting themselves to Canadian law, which attorneys are expected to follow at the risk of contempt of court. As Mohawk Mother Kahentinetha told me: “I don’t go to court because the white man’s laws apply to me. I go to court to force the white man to follow his own laws.”

The Right not to be Represented

The colonial state’s initial response to the Mohawk Mothers’ March 25, 2022, originating application was to file a motion requesting them to be represented by a lawyer. The motion cited article 87 of the Code of Civil Procedure, which states that while individuals can represent themselves in court, all organizations, legal persons, or “other groupings not endowed with legal personality […] are required to be represented before the courts by a lawyer in contentious proceedings,” thus granting a professional monopoly to lawyers to represent any group, unless all of its members give their written consent (Kahentinetha et al. v. SQI et al. 2022a). According to the Attorney General of Quebec’s submissions in court, this request was not intended to limit the plaintiffs’ access to justice, but to protect Indigenous people from an unfavorable judgment if their rights were defended by unqualified and unrepresentative persons.

As a response, the Mohawk Mothers submitted in court that the notion of representation does not apply to their situation, as it has no equivalent in their language and culture. They stressed that they do not represent anyone, on the contrary, their tradition prohibits them both from representing and from being represented by anyone. In fact, they explained that their tradition forbids them both from being told and from telling others what to do,13 as everyone is expected to “freely” and “autonomously” assume their duties and responsibilities to their people and to non-human beings on their territory (animals, plants, rivers, etc.). Noteworthy is the paradoxical coincidence between the Kanien’kehá:ka understanding of “freedom,” Tewatatewenní:io, and obligation here, as individuals are obligated to act freely in order to truly be responsible for their actions in the absence of a power of attorney delegating or representing their willpower. In this Kanien’kehá:ka sense, diametrically opposed to the European one, the social responsibility of individuals is proportional to their degree of personal autonomy; that is, their capacity to act upon their own will without oversight. This capacity is bolstered by the situated knowledge of the social and ecological environment in which specific groups reside and interact. For example, it is said that members of the turtle clan (Ratiniáhton) are tasked with submitting issues to the council, because having neither claws nor fangs, turtles must decide rapidly whether they have time to jump in the water to escape a predator or should instead shelter within their shell.

In reaction to the government’s motion to force them to use a lawyer, the Kahnistensera amended their originating motion:

The Plaintiffs’ self-representation in legal proceedings is a compulsory requirement following the kaianerehkó:wa (“Great Good Path”) and kanien’kehá:ka cultural practices, customs and traditions.[…]

Wampum 58 from the kaianerehkó:wa provides that “Any chief or other persons who submit to laws of a foreign people are alienated and forfeit all claims in the Iroquois nations”. Persons who submit to the laws of a foreign people are called “They have alienated themselves” (Tehonatonkoton) and “shall forfeit all birthrights and claims of the League of Five Nations and territory.”[…] This provision prohibits kaianerehkó:wa people from using attorneys who pledge oaths to foreign laws as intermediaries for pursuing their traditional duties and responsibilities.[…]

The Plaintiffs do not represent anyone in the corporate-based meaning of “representation” used in Canadian courts, which has no equivalent in kanien’kehá:ka culture. Used in ceremonial as well as legal and diplomatic settings, the kanien’kehá:ka word Tewatatewenní:io, meaning “we are all free”, “we are all sovereign”, and “we all carry ourselves”, determines that all Indigenous individuals speak for themselves as free people and cannot be represented by others. This natural freedom makes all kanien’kehá:ka individuals all the more responsible for fulfilling their traditional duties in accordance with the kaianerehkó:wa and oral tradition. It must be noted that the kanien’kehá:ka tradition considers freedom as a natural birthright granted by creation rather than a sovereignty granted by any human institution.[…]

The Plaintiffs’ self-representation in court proceedings is thus based on their individual responsibility to freely exert their constitutionally-protected cultural duty as kahnistensera (kanien’kehá:ka women).

The fact that the definition of representation which prevails in Canadian courts is inconsistent with kanien’kehá:ka culture, where attorneys do not exist, makes it impossible to represent and confiscate the free will of all members of an Indigenous people in decision-making. For this very reason, treaties made in the past between representative of the Crown and select Indigenous individuals deemed to be “chiefs” are null and void, as they failed to obtain the consent of all free Indigenous people. Any single person signing a treaty on behalf of an Indigenous group, clan or people violates the kaianerehkó:wa, which outlines the due protocol for clan-based consensual decision-making. (Kahentinetha et al. v. SQI et al 2022b).

The man-made laws of the courthouse ship are made null and void when faced with this Indigenous duty of responsible freedom and “autonomous responsibility”14 as a cornerstone for consensual collective cohesion. According to Tekarontakeh, the word for “mothers,” Kahnistensera, literally means “life givers,” coming from O’nísta, which refers to the point where the umbilical cord is attached to the mother, making the connection between women and Mother Earth akin to the stem that connects the apple to the tree (Karoniaktakeh 2023, 263). As the Earth is a mother, all the plants that grow from her are also feminine: the “big sisters” like wild strawberries that take care of themselves, as much as the “little sisters” that need to be tended to, such as corn, squash, and beans. On the other hand, men are modeled after the sun, bringing warmth and light to the women’s land. Rather than liabilities, freedom and autonomy in the Kanien’kehá:ka sense are understood as prerequisites for the fulfillment of these specific duties, ensuring that they will be respected without the need for coercion.

The Mohawk Mother’s argument that all treaties are null and void curiously echoes the way in which the Code of Civil Procedure stipulates that all members of a group must give their consent to be represented: in a lawyerless society, where one can only represent oneself, or rather present oneself, one cannot relinquish another person’s birthright to speak for her or himself. Every single person would have to sign a treaty for it to be valid. In the Ganienkeh Manifesto, distributed to the United Nations in 1974 after Mohawk warriors reoccupied their ancestral lands in the Adirondacks, Karoniaktajeh (2023, 133) denounced the actions of Joseph Brant, a Mohawk who maintained close ties with the British during the American Revolution. Brant had leased out most of the Haldimand Tract, initially reserved for the Rotinonhsión:ni who were expelled from the United States. He had granted himself a “power of attorney” without submitting the matter to council, whose procedures precisely and consistently work to nullify any such power of attorney, following the principle that decisions are only binding if they are freely accepted.

No Fire Without Embers

The story of the origin of the Kaianerehkó:wa (“Great Good Path”) and the formation of the Rotinonhsión:ni confederacy recounts how Deganawidah, Hiawatha, and Jigonhsasee put an end to the bloody wars between the Five Nations through words and wampums of “condolence,” allowing to overcome the grief and cycles of vendettas following the loss of relatives. Snake-haired war-mongering Onondaga chief Atodarho, literally the “Entangled,” was the last leader to join the alliance, as he was persuaded to become the “first among equals,” with the privilege of gathering all families in the Grand Council in Onondaga. Atodarho was also granted the right to veto any decision, although this privilege was annulled by the fact that “any chief had a virtual veto on any proposal before the council” (Tooker 1978, 422). Yet the term “chief” is misleading, as his discretionary power rather rests within the families whose positions chiefs merely present to the council. The Kanien’kéha:ka term for chief, Roiá:ner, rather means “he has a path” (Karoniaktakeh 2023, 265), and the forty-nine permanent titles determining the chiefs’ specific roles within the Grand Council belong to the clans themselves – and chiefly the women, who are responsible for both selecting and deposing them. Therefore, chiefdom does not involve any representation or transfer of power, which remains within the family, who consensually determines the content of the “bundle” which their Roiá:ner carries to the council.

At every step of its concentric, onion-layered consensual decision-making system, comprising no less than 117 wampums in Parker’s first written version (1916), the Kaianerehkó:wa applies a Two Row-based principle of reciprocity wherein all constituencies, and chiefly the five nations themselves, are at once bound together and kept separate, conserving their freedom to conduct their own affairs while uniting against common threats. The Grand Council’s longhouse is divided in three sides: the Elder Brothers (Seneca and Mohawk, larger nations), first take the issues submitted by the people in the well at the center of the longhouse, and share their position with the Younger Brothers (Cayuga, Oneida, and Tuscarora, smaller nations), who then submit their opinion to the Onondaga “firekeepers.” In smaller scale national or community councils, the same tripartite model applies as the longhouse is rather divided between clans – Bear, Turtle, and Wolves, in the case of the Kanien’kehá:-ka.15 Whenever an opposition arises as the proposals bounce to the other sides of the longhouse, the process must start all over again. If speakers are unable to “roll their words into one bundle,” they must set the issue aside and the council fire is “covered with ashes” (Tooker 1978, 422).

This reference to ashes is not a mere metaphor (Tuck and Yang 2012), as the very term for the council, Kahwá:tsire’, literally means a “gathering of embers,” and designates both a family and a fire, originally referring to the family’s hearth in the longhouse. A family fire is created when individual embers, Ó:tsire’, come together to create a flame and intensify the heat. The Grand Council, which brings all the Kahwá:tsire’ together, is called the katsenhowá:nen, the “big fire,” according to Kanasaraken (Karoniaktajeh 2023, 260). Most importantly, when a decision seems to have been reached and the fire looks extinguished, the council must “stir the ashes” to make sure that no ember is still burning, asking each person who has not yet spoken to express their point of view.16 This is not only to deepen and validate the consensus, but to enrich it with the singular perspectives of all individuals, whose participation is strongly encouraged, if not compulsory.

The Kaianerehkó:wa ingeniously telescopes the individual into the community, and viceversa, by locking centrifugal and centripetal forces of allegiance and accountability into one another. Morgan (1877, 135) suggested that the Rotinonhsión:ni just had one step left to join civilization, which was severing the link between their body politic and the families, which he considered the most “primitive” unit of organization. Yet it is by way of this chain of commandment, flowing back and forth from autonomous, self-governing family units to larger or foreign autonomous, self-governing bodies, that the Kaianerehkó:wa staves off any power of attorney and representation. Stirring the ashes is to “call into presence” the people to present their views. It is a “roll call” not only of the chiefs, but of everybody.17

The notion that each individual’s role and responsibility mirrors that of a Roiá:ner is apparent in Rotinonhsión:ni name-giving ceremonies, which bestow individuals with unique names that no one else must possess, marking their personal mission from the moment that infants start to express their singular perspective in the world. Each individual name is a sovereign title of sorts residing in each person’s “mind,” O’nikòn:ra’, a term meaning “protection” and alluding to the husks protecting the corncob. Just as a Roiá:ner’s title, individual names are under the custody of their clans, and imply roles, rights, and responsibilities which belong to the entire family (Tooker 1978, 424). This is why individual views are paramount in supporting a decision, broadening its horizon, and ensuring that it will be implemented freely and effectively. This is why, moreover, one’s particular mind, reflected by their name-title, cannot be delegated to anyone else: tóhsa sathón:tat naiesa’nikonhráhkhwa, “don’t let them take your mind/protection,” as Tekarontakeh recalls being told by his grandfather (Karoniaktajeh 2023, 15).

That there are no representatives or attorneys among the Rotinonhsión:ni means that each one acts both as legislator, executor, and judge. In particular, the women retain “what amounted to a judicial review of men’s actions” (Goettner-Abendroth 2012, 306), as their position conveys the consensus of all members of the matrilineal family fire, the fundamental unit of Rotinonhsión:ni politics on which larger circles of decision-making rest. The assembly or council – whether judicial or political, colonial or traditional, does not matter, as all powers consistently rest within the unanimous sum of the people’s minds – is the locus where their ideas are presented and balanced with a view to a “unity in multiplicity,” where decisions are all the more binding that they are freely accepted.

Every House is a Longhouse

How does the responsibility of an ember, Ó:tsire’, to its fire, Kahwá:tsire’, translate in court? While the minutes of the Superior Court indicated all moral persons as “absent,” as they were represented by their attorneys, the Kahnistensera were all “present.” They argued that it was their cultural duty to be present, making use of their social positions, experiences, and way of thinking, to carry the bundles of their families in the settlers’ ship. Complexifying Hannah Pitkin’s (1967) classic definition of representation as “making present again” an absent voice, Louis Marin (1981, 10) distinguished between the “transitive transparency” which re-presents an absent voice “as if” it was present (political representation), and the “reflexive opacity” by way of which “any representation presents itself representing something,” effectively duplicating, replacing, and supplementing an absent voice by its public display (legal representation). In the Kahnistensera’s court submissions, the double negative of “self-representation” cancels its duplication. They are not not present. If someone happens to disagree with them, they are also free to step up and speak on their own behalf, because just like people cannot tell others what to do, they can always start their own fire, transforming a potential veto in the affirmation of another position.18

The Kahnistensera claimed their right to refuse the translation of legal representation and powers of attorney into their culture, but what would it imply to reverse the burden and ask the court to account for the Kahwá:tsire’? The Two Row Wampum proposes an Indigenous-led pathway for transcultural analogies, providing settlers, by way of a naval imagery they could also relate to, insight into Indigenous relationalities. It is thus no surprise if its paradoxical notion of alliance through separation addresses the core conundrum of cross-cultural translation. For instance, Silverstein (2003) proposed “transduction,” based on an analogy with a motor engine’s transducer, as a method to translate worlds made of entirely distinct energies, each requiring their own methods – with a view to drawing analogies between each world’s own world of analogies. According to Gal (2015, 233) transduction seeks to avoid forced commensurations seeking equivalences by placing “items on a grid or scale that gauges them with respect to each other.” Similarly, Viveiros de Castro (2004, 10) calls “controlled equivocation” a method that, instead of annulling divergences between languages (which differ alongside the worlds they speak from and about, the signified floating as much as the signifier), would “emphasize or potentialize the equivocation” to present the untranslatable, non-equivalent, and irrepresentable as such, transporting non-identity into the final product. As “there are no points of view onto things, things and beings are the points of view themselves” (11), equivocation makes points of view present rather than represented, in court as in council, to account for the worlds behind words, or the “paths” behind “laws.”

The Two Row Wampum expresses the limit of legal pluralism (Lemieux 2012), resisting its translation by and into the legal metalanguage as a right among others, where we are “all in the same boat.” Yet the Two Row’s horizon, by potentializing difference, remains to build alliance. The more difference is respected, the stronger the alliance. The more the gap between worlds is minded, the greater power their potential difference can generate. In that sense, the Kahnistensera’s assemblies, by stirring the ashes, apply the Two Row to themselves, to widen the scope of their internal differences into an allied front.

The Kahnistensera displayed this paradoxical power of potential difference in their response to the fifty-five cross-examination questions that the Attorney General of Quebec sent on September 7, 2022, to Kahentinetha, who had filed an affidavit as a witness of medical experiments on Indigenous children. Instead of addressing these sensitive issues, Quebec sent a series of textbook questions regarding the official structure of the Rotinonhsión:ni government, asking the Kahnistensera if they had the approval of their chiefs to initiate the lawsuit.

Several questions painstakingly tried to identify official traditional Rotinonhsión:ni bodies, such as the Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs, registered in Akwesasne, whose approval would be required for the Kahnistensera to be legitimate. Kahentinetha, however, simply responded that the “neither the Kaianerehko:wa nor our precolonial oral tradition refer to the Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs”, and insisted that “we all represent ourselves.” To question 9, which asked whether these “Chiefs represent the Mohawk Nation in the Confederacy,” she answered “They do not ‘represent’ the Mohawk Nation. They are supposed to carry the voice of the people.” When asked which longhouse she attended and who was its chief, Kahentinetha responded “There are no chiefs. As a free people we can all have meetings anywhere, anytime. Buildings and villages do not make us who we are,” adding that:

We say that there is only one longhouse that begins where the sun rises and ends where the sun sets. The sky is its ceiling, and the ground is its floor. For us there is only one longhouse for the people, it is A’nowarà:ke (Turtle Island). On another hand, if you are talking about physical buildings, there are thousands of buildings in Kahnawake so there are thousands of longhouses. Meetings can happen in any house. (Kahentinetha et al. 2022c)

This symbolic longhouse transcends any designation of an exclusive, sacred space for meetings, as any building can make the symbolic longhouse present. I was told not uncommonly by longhouse people that their elders said when they were young that if there was just a single Indigenous person left, that person would still have custody of the entire territory. Tradition makes itself present through a single individual, as a shard or fragment reconstituting the whole. Responding to question 21, which asked who were the Kahnistensera (Mohawk Mothers) and whether they were authorized by official clan mothers, Kahentinetha wrote: “All the women are Kahnistensera.” As she began her oral arguments in court, Mohawk Mother Kwetiio similarly gestured towards all the Indigenous women in the courtroom, emphasizing that all of them were equally Kahnistensera, explaining that it is not a group that anyone could represent, but a shared responsibility and a shared power to protect the land and the children, which everyone is expected to uphold autonomously.

To conclude, I propose a response to question 12, which Kahentinetha objected to. It inquired whether any of the current official chiefs from the Mohawk Nation or the Grand Council were from Kahnawá:ke. The answer is “No”, and it is not a mere coincidence that Kahnawá:ke, established as a Jesuit Catholic mission by the French in 1667, evolved into a society without traditional chiefs while seeing the emergence of significant militant figures such as Karoniaktajeh, Tekarontakeh, and the Warrior Society. Doing research on the use of Indigenous children as test subjects at the Allan Memorial Institute, I stumbled on ethnographies of Kahnawá:ke written by two McGill professors in collaboration with Canada’s Defence Research Board. Anthropologist Fred W. Voget (1951, 221) described Kahnawá:ke as an ideal site for studying nativist movements because of the “concentrated acculturation to which the inhabitants have been subject for almost three hundred years,” while sociologist Oswald Hall’s study of “The Industrialized Indians of Caughnawaga”19 focused on the unruly behaviors of its inhabitants, stating that “In the first instance the reservation seems to be organized around hostility toward the federal government”, and that “the reserve displays a volcanic uneasiness. It is marked by recurrent disturbances of a minor riot character” (Hall 1949, 10).

It would seem that Kahnawá:ke’s putative acculturation and nativist authenticity somehow coincide, as traditional Kaianerehkó:wa families, surrounded by Christian converts and French settlers, took shelter beneath the Tree of the Great Long Leaves to covertly pursue their tradition in its essential form, without relying on overt governance structures. It goes to show that the Kaianerehkó:wa (“Great Good Path”) endured primarily through the minds, hearts, uses and practices of the people, freely carrying their responsibilities and longhouse on their back. Such is the power not to be represented which every Rotinonhsión:ni holds, and which Justice Moore acknowledged on September 20, 2022, by rejecting the defendants’ request for the Kahnistensera to hire a lawyer, so they can fulfill their “individual obligations to watch over the traditional territory of the kanien’keha:ka people and to protect the children of the past, present, and future.”

Author

Philippe Blouin writes, translates, and studies political anthropology and philosophy in Tionni’tio’tià:kon (Montreal). His current PhD research at McGill University seeks to understand and share Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) traditional teachings, and specifically the Teiohá:te (Two Row Wampum), to build decolonial alliances. Since 2021 he has been involved with the Kanien’kehá:ka Kahnistensera (Mohawk Mothers) to investigate disappeared Indigenous children and protect sites potentially containing unmarked graves. He has published essays in the South Atlantic Quarterly, PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, and an afterword to George Sorel’s Reflections on Violence.

philippe.blouin@mail.mcgill.ca

PhD Candidate, Anthropology Department, McGill University