Indigenous assemblies in the Peruvian Amazon are one of the main institutions where indigeneity is being manufactured as a political form of agency. It marks a strategic and foundational moment in indigenous politics, not only for its capacity to “assemble” diverse groups and tribes into a cohesive political body but also for its role in reshaping the traditional animosity these groups once held towards each other (cf. Descola 1993).

A clear example can be found among the Amerindian groups previously named “Jivaro” in the Northern Peruvian Amazon. Their reputation for warfare needs no further evidence. Any traveler, whether an ethnologist or not, is often struck by their vigor and the occasionally confrontational nature of their interactions, particularly within the political sphere, even to this day. The stories their men declaim are peppered with martial prowess, typically recounted in the first person (Hendricks 1994; Taylor 1993; 2006). Their history is one of rebellious tribes, resistant to the efforts of the Incas, Jesuits, and conquistadors to subdue them. It is a history haunted by the prospect of war, punctuated by the practice of vendetta and headhunting, structured by the law of reciprocity in aggression—by which those who now refuse the exonym “Jivaro” have persisted in their identity. They now ask to be called Aénts Chicham (Deshoullière and Utitiaj Paati 2019), which can be translated as “people of the word.” Their sociability is no longer defined by warfare and bloodshed but by negotiations, more or less violent depending on the circumstances, aimed at securing the conditions for their survival and eventual autonomy. To accomplish this, they had to shift their tactics, moving away from warfare and embracing the tools of diplomacy—pens, paper, the law, and persuasive speech (Greene 2009). The former warriors became community organizers, teachers, political representatives, lawyers. They have adopted ad hoc legal frameworks, such as federations and assemblies, to establish themselves as a political force across all levels, ranging from the local to the international. They have, in this sense, evolved into “people of the word” (Aénts chicham), but the unequal dynamics in their interactions with the state and in front of external economic pressures still leaves them in a situation of “uncertain peace” (Brown 1984).

This condition was brutally underscored through the violent conflict that erupted between Amazonian indigenous peoples and the Peruvian state in June 2009.1 The clashes followed prior attempts at negotiation between the state and indigenous representatives. The indigenous groups organized various demonstrations, including protest marches and blockades of roads and oil exploitation sites. They united to oppose state measures imposed without consultation. For indigenous communities, this marks the culmination of a political evolution that originated in the 1970s, empowering Amazonians to establish political organizations that assert their unity amidst the ethnic diversity that defines the Peruvian Amazon.2 The fact of such a conflict itself—where Amazonian indigenous peoples oppose the state as a whole—indicates the emergence and consolidation of indigenous self-awareness within the political landscape.

Here is where the significance of indigenous assemblies becomes notably evident. According to some analysts, political assemblies appear to primarily serve the purpose of fostering collective self-reflection, leading to the emergence of a unified “we, the people,” in other words, the acknowledgment and assertion of a common political identity (Detienne 2003, 16). In the case of Amazonian indigenous peoples, this unique and hybrid institution is precisely one of the arenas where political self-awareness has been cultivated over the past few decades. Yet, assemblies often do not receive as much attention as indigenous leaders or federations, despite the fact that the latter largely emerge as a result of assembly dynamics. With a few exceptions (cf. Morin 1992a; Belleau 2014, 137–65), research on contemporary indigenous politics in the Amazon often overlooks assembly dynamics, prioritizing instead leadership (cf. Chaumeil 1990; Greene 2009; High 2015; Veber and Virtanen 2017), institutional history and structure (cf. Chaumeil 1987; Morin 1992b; Romio 2014), or cosmopolitics (cf. Surrallés and García Hierro 2005; Sztutman 2012; Oakdale 2022).

These subjects are undoubtedly intertwined, and a comprehensive analysis of indigenous politics should integrate them harmoniously. However, indigenous assemblies hold a specific significance, serving as the platform where indigenous peoples not only engage in debates and voting, but also distinguish between direct democracy and representative elections. These assemblies serve as the arenas where a collective force undergoes constant reconfiguration, both in its decision-making processes and its institutional structure. It provides a space for indigenous people to define their shared indigeneity and the form of their autonomy amidst internal tensions and divisions. Indigenous assemblies serve as the embodiment of “the people,” thereby bestowing legitimacy upon any representative indigenous authority, whether it be a leader, a federation, or even an elected official.

One of the major regional indigenous political organizations that has emerged in the Peruvian Amazon is the Regional Coordination of Indigenous Peoples (CORPI3) (Fig. 1), which is located in a region dominated by Aénts Chicham peoples.4 This dominance is also reflected in the leadership of CORPI, which has been predominantly led by Aénts Chicham leaders, particularly Awajún5—a fact that has sparked internal tensions. In any case, CORPI offers a vantage point to investigate the role of indigenous political assemblies and their contribution to the development of collective self-awareness. But in this equation, it is crucial to consider the customary Aénts Chicham element mentioned earlier: the factor of hostility. By “hostility,” I mean here a specific attitude towards others, which is characterized by a display of antagonism, a dominant stance, and unwavering determination (cf. Taylor 2007, 146–47). It doesn’t always imply bellicosity or the designation of the other as an “enemy,” but it is a way of presenting oneself to others in order to establish a specific relationship with them. Even in times of peace, the specter of war persists: in the Awajún language, the term for peace, nagki atukbau, translates to “laying down my spear”—a ceasefire maintained with the awareness of the ever-present threat of conflict.

Figure 1: CORPI’s headquarters in San Lorenzo, Loreto (2011), (Photo credit: Thomas Mouriès).

Hostility is not confined to external interactions: it also shapes internal social dynamics to this day. For instance, the suspicion of witchcraft examined by Simone Garra among the Awajún (Garra 2017) serves as a manifestation of this inherent hostility within the ongoing socio-economic transformations of indigenous communities. The question then becomes: How does this hostility contribute to the formation of a shared political identity that brings together former tribal enemies? The main answers to this question can be found within indigenous assemblies, because they are collective spaces where the need to come together meets the fact of division, and where politics emerges as a display of both compromise and opposition.

But to explore this issue, we must first understand how Amazonian politics is organized in contemporary Peru and identify the institutional tools through which indigenous people define common goals and engage in collective action. We will look at how indigenous organizations work together regionally and examine the challenges they face in creating a heterogeneous political collective under the common banner of indigeneity. I will show how different levels of indigenous organization imply different political models: at the regional level, direct democracy as practiced in local communities is no longer relevant, but neither is the idea of a strictly ethnic representation, which is still practiced in most local federations. Indeed, starting at the regional level of the indigenous political organization, choosing a leader and an executive board to unite diverse ethnic and geographical groups involves navigating internal disagreements and hostility.

The Indigenous Political Organization, From the Bottom to the Top

Contemporary indigenous politics in the Peruvian Amazon is built on a system of interlocking federations of different scales. Local “bases” or grassroot organizations are affiliated with a regional organization, which in turn is affiliated with a national organization, such as Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), the main indigenous confederation in the Peruvian Amazon.6

Indigenous assemblies periodically decide on the federations’ leadership and strategic direction. Once a year (depending on the financial means), these assemblies bring together the “bases” of a specific indigenous organization. For a local federation, the apus—leaders of the indigenous villages—form these “bases;” for a regional federation, the bases are represented by the leaders of the local federations; and, for the national federation, it is a mixture of leaders from both local and regional federations. Each federation has its own assembly, which is responsible in particular for constituting, dismissing, or reappointing the federation’s executive team.

Legally, each indigenous federation is a non-profit association headed by a five-member executive board.7 The visible head of the federation is the president of the board. After the president, the vice-president also has an important role, replacing the president in their absence and acting as interim president when the president’s mandate is interrupted. The other members are also indigenous “leaders” in the full sense of the word, as they have been elected by their constituencies during an assembly, which gives them recognized political representativeness during their term. In principle, the real decision-making power is not held by the president alone, but by the complete team, which is considered the only legitimate executive body.

While my fieldwork8 uncovers a more intricate reality, it remains a fact that within indigenous federations, leaders elected every four years in a plenary assembly embody one of the primary institutionalized figures of indigenous leadership in the Peruvian Amazon. These leaders—primarily the federation presidents—perform various administrative and representative functions. They act on behalf of their federations and their constituents, and occasionally (but not without tension and misunderstanding) on behalf of the indigenous Amazonians as a whole. Such was the case during the conflict that has already been mentioned here: in 2009, in the Amazonian province of Bagua, the armed forces and the police attacked indigenous protesters who were blocking a strategic departmental road, which ended in a bloodbath, leaving more than thirty people dead and hundreds injured. At the time, Segundo Alberto Pizango Chota, who was at the head of AIDESEP (national), was seen as “representing” the Amazonian indigenous peoples, and he was forced into exile.

The Apu and the Leader

Amazonian indigenous leaders are always elected in a plenary assembly. The AIDESEP (national) assembly is made up of the leaders of the regional and local federations, most often their presidents, who elect their national representatives. Likewise, the CORPI (regional) assembly comprises the leaders of the local federations (the CORPI “bases”), who in turn elect their regional representatives. At the regional and national levels, the assemblies are composed mainly of federation leaders who have already been appointed by an assembly with a representative mandate within the federation system. This suggests that the production of leaders through the indigenous federation system is an endogenous process.

But the federation leaders are not the only type of indigenous leaders—although they are the most visible, perhaps even the most powerful, given the strong institutional system that supports them. The foundation of the entire political system resides in the indigenous communities (comunidades nativas9) and the comuneros who live there. These communities, which population can range from a few dozen to several hundred, can be defined as “[a]n organization with legal status made up of a group of people with ancestral ties, which occupies a certain territory in the Amazon rainforest and maintains its traditions and forms of organization.”10 From these communities emerge a first type of indigenous leader in the Amazon, called apu, a Quechua word designating in this context a political authority.11 The apu is elected by the village assembly as the community’s legal representative. His function is mostly administrative, which is why he is usually a young, literate, and ambitious indigenous person rather than an older, experienced one.12

But how could a young, educated, bilingual native “represent” the whole community? The role of an apu is not to lead, but rather to mediate and deal with administrative issues. The apus do their work and make decisions under the guidance and often the direction of the community. They act as “representatives,” more in terms of direct democracy than representative democracy: that’s why they are chosen mainly for their abilities as facilitators and translators. The true authority is the village assembly as a whole, and the apu is the executor of a collective will, not its guide, and certainly not its chief (cf. Clastres 2013). This shows once again the importance of assemblies in Amazonian indigenous politics, where authority is delegated only as a last resort, and where the group, in its process of consolidating itself, refuses to be led by an individual, whether charismatic or not.

In short, there are two different types of leaders: federation leaders and apus, and two corresponding types of institutions: the indigenous federation and the indigenous local community. Once elected by an assembly, however, the indigenous leader must leave his community for the federation headquarters and a nomadic life, moving at the whim of meetings and negotiations his mandate requires. Unlike the apu who remains a comunero without compensation for their office, the leader becomes a politician who is compensated monetarily for their role in the federation, albeit with varying degrees of difficulty. It is important to note these differences in leadership and institutions to better understand the intricacies of indigenous governance.

The Indigenous Assembly: A Collective Body

There is no higher authority than the indigenous assembly. This was said by a municipal councilor during a meeting I attended in March 2012 in the Pastaza region (Department of Loreto): “La asamblea es la máxima autoridad!” The fact that an elected official and agent of the state asserts the supremacy of the assembly over any other institution and individual, including public authorities, emphasizes how such an indigenous institution symbolically and politically transcends the framework of indigenous federations: it is both a part of that political system and its foundation. On that day, the Quechua federation FEDIQUEP13 was holding its annual assembly (Fig. 2) and had invited the provincial mayor and his team to participate. The mayor, himself an indigenous Quechua, wanted to leave after the first day, but the assembly asked him to stay. His councilor recognized then the political relevance of the assembly, and the team remained another day.

Figure 2: Community delegates and apus attending a federation’s assembly (2012), (Photo credit: Thomas Mouriès).

The indigenous federation system starts at the local federation level. Unlike regional or national federations, for example, the local federation does not represent other federations: it represents indigenous communities that have decided to join the federation according to political, ethnic, and geographic criteria.14 In my study of an indigenous assembly (Mouriès 2016), it was noted that the village chiefs or apus convene for a period of approximately five days once every two years. They attend the assembly accompanied by two to five members from their community, and all residents of the hosting village join in, forming a substantial “popular” constituency from which the political authority of the local assembly emanates. The mode of political representation undergoes a noticeable shift between indigenous communities and their corresponding local federation. Indigenous politics transition from customary leadership15 within the community to institutional and extraterritorial leadership beyond it. This transition also involves a shift from a “direct” to a “representative” mode of democracy. In this way, indigenous politics becomes part of the broader context of Peruvian politics and builds democratic legitimacy, enabling indigenous leaders elected under the federation system to negotiate with the state on behalf of their Amazonian constituents. Yet again, indigenous politics demonstrates a deep-seated distrust towards representative systems. Assemblies thus become the primary arena where this skepticism can be voiced and, potentially, reconciled.

This is why the “bases” become an essential factor of political legitimacy: they embody the founding ground of indigenous politics, the place where it all began, the primary source of political authority. Local assemblies are supposed to be the embodiment of “the people,” the time and place where authority is given by those who are represented to those who will represent them: the foundation of representative politics. Wouldn’t then the true heart of the bases lie in the village assembly, and not in the local federation one? The former gathers community leaders, while the latter gathers the community itself. We find already a nascent representative politics in local federation assemblies, when communal assemblies are attended by most villagers and not just their delegates. But a village assembly deals mainly with the day-to-day concerns of the village and its surroundings, without any major impact on indigenous politics as a whole. If it does, it is only circumstantial. This is not the case with a federation assembly. Indigenous federations articulate local, regional, national, and even international levels, so that the issues debated in the assembly, while tending to concern geographically circumscribed questions, nonetheless involve a much broader and more ambitious indigenous vision, touching on what Marc Abélès calls the “new global politics.”16 The leaders are the bearers of this vision and the operators of its implementation. Additionally, as observed, the apus primarily serve as facilitators and spokespersons rather than authoritative leaders. This dynamic blurs the traditional notion of “representation,” as apus speak not so much on behalf of their constituency but rather under its direction. Thus, by bringing together the two circuits—the “grassroots” communities, that is, the villagers themselves, and the federation system—, the assembly of a local federation is a strategic moment in the political life of the indigenous Peruvian Amazon.

The assembly stands as a pivotal moment fraught with tensions and challenges: it represents the original locus of power delegation within the political framework of indigenous communities. This entails the establishment of a mode of (representative) power, which comuneros seek to counteract in their daily lives.17 In the local assembly, we go from a territorialized legitimacy, which remains under control inside the village, to a representative legitimacy which is subject to suspicion, because, as long as it remains far from its constituency, it threatens to betray its mandate. That’s why the assembly (and particularly the assembly of a local federation) transforms its temporary incarnation into a spectacular showing of supreme power, a power that is capable of overthrowing a leadership team or of subjecting to its will any indigenous participant, including an official agent of the state. In the Amazonian federative system, if there is indeed a pyramidal institutional structure, the assembly serves as a moment of truth where the pyramid is inverted. It’s when the “bases” converge at the summit, a unique occurrence—but only for a few days every couple of years.18

A Laboratory of Indigeneity

Assemblies also serve as the arena for implementing indigenous autonomy, driven by two main reasons. Firstly, during an assembly, indigenous people debate, disagree, and compromise on indigenous issues, without being directly influenced by non-indigenous agents—mainly by internal advisors and external partners, two strong figures in the federation system. Secondly, the assembly stands as the site for constructing political legitimacy; it’s also where the essence of political indigeneity is continually shaped and reshaped.

This applies to local, regional, and even national indigenous federations. The main difference between the assembly of a local federation and that of a regional federation lies in the homogeneity of the latter: at a regional federation’s assembly, there are almost only leaders already elected by their bases and belonging to the federation system. This does not mean that elected federation leaders are the only ones who participate in the regional assembly, but they are the only ones whose voices and votes count. The political influence of the comuneros, apus, and indigenous communities begins to dissipate here, although leaders frequently allude to the community bases that elected them and from which they derive their political legitimacy. Yet, within the framework of representative democracy, the existence of these bases is now merely spectral.

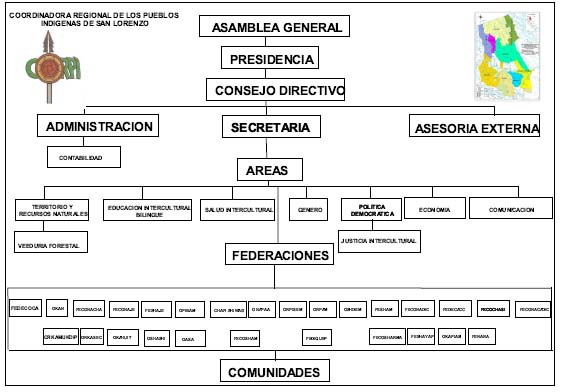

But the specificity of the regional level of governance, positioned between the local federations and the national indigenous organization, holds its own legitimacy and significance. At this intermediate level, a fundamental operation of indigenous politics unfolds: the production of indigeneity as a political-legal category, capable of bringing together a diversity of indigenous groups that were traditionally at war, and that find a laboratory for developing a common agenda in this space. If we take the example of the CORPI federation, we can clearly see in its organizational chart (Fig. 3) that it aggregates different entities: the general assembly oversees the presidency of the federation and the executive council, which consolidates several administrative functions, several work programs and, above all, a large group of indigenous federations, which themselves come from the various communities they represent.

Figure 3: CORPI’s organigram in 2011 (Source: CORPI, internal document, 2013).

The architecture of the regional federation thus appears to be primarily concerned with managing diversity, bringing it down to a measure of unity that satisfies its different constituents—especially the local federations—and its different partners—the external advisors and funders. This unity is primarily provided by indigeneity as a political abstraction, because indigeneity is not an intuitive notion: there is both a conceptual and an institutional process to go from “I am Awajún” to “I am indigenous,” because “I am Awajún” traditionally implied that “I am not Achuar” or “I am not Wampis”—these entities used to be positional antagonists who need each other, in the context of tribal war, to define themselves by opposition. Indigeneity transforms these contrasting definitions of the collective by introducing a distinct positional system: “we, the indigenous people” is now opposed to the White and the “mixed blood” (mestizos). Indigenous politics implies a reconfiguration of these identities, requiring ancestral relationships to be progressively disentangled and reassembled within another system of reference. The political, legal, and economic consequences of this transformation is what makes indigenous politics what it is today: it brings together a diversity of ethnic groups, it connects them to national and international human rights, and it makes them eligible for development aid programs.

Unlike some local federations’ assemblies, the matter at CORPI is no longer to know what it means to be Quechua of the Pastaza, or Awajún, or Shawi, etc., but to find how all these belongings can share “indigeneity” as a common denominator. CORPI emerges as a crucible where the evolving definition of indigeneity unfolds through diverse ethnic affiliations, influenced by the prevailing adversarial stance inherent in the Aénts Chicham ethos. CORPI brought together nine indigenous peoples whose histories were characterized by intertribal conflicts (Taylor 1985; Julou 2006; Taylor 1999; Seymour-Smith 1988; Ochoa 2009): the Aénts Chicham groups (Achuar, Awajún, Wampis), those related to them (Kandozi, Shapra), as well as their neighbors (Kukama-Kukamiria, Pastaza Quechua, Shawi, Shiwilu). This unity first cracked with the departure of the Achuar in 1997, who formed their own supralocal federation (Federación de la nacionalidad achuar del Perú, FENAP). Although no defection of this magnitude has occurred since, a centrifugal inclination persists, particularly during assemblies, whose agonistic nature I aim to delineate through two ethnographic examples.

During the 2011 and 2012 CORPI assemblies, which I had the opportunity to attend, there was a vote each time, though on different issues. In 2011, a vote was planned to designate CORPI’s candidate for the presidency of AIDESEP, the national federation, which would take place during the renewal of AIDESEP’s executive board the following month. In 2012, with the term of the CORPI leadership team nearing its end, the need arose to elect a new executive board, including a new president. Each of these assemblies resulted in a demonstration of hostility, directly challenging the unity CORPI is meant to foster.

CORPI and the National Federation: How to Nominate a Candidate?

Just before concluding its annual meeting in November 2011, the national federation (AIDESEP) visited the indigenous federation CORPI at its headquarters in San Lorenzo. Represented by its treasurer (an Achuar from the Corrientes River), the national federation aimed less at strengthening ties with its regional base than at campaigning for a second re-election of its current president (Alberto Pizango Chota), who had previously been CORPI’s vice-president. CORPI’s leaders were not fooled, and several of them denounced the lack of interest of national federation representatives outside of the election period. The national federation’s leader avoided confrontation: he himself was working for re-election as part of the executive board.

CORPI’s distrust of the national federation was evident in the exchanges that took place on November 24, 2011, after the national representative ended his short visit. A highly regarded Awajún leader from the region set the tone by reminding the assembly that “in any organization there are those who betray,” while a former president of CORPI emphasized that the national federation had changed its rules at the last minute to allow the re-election of its current leadership. AIDESEP’s visit highlighted the regional federation’s frustrations with the national organization and the lack of representation and legitimacy of AIDESEP. The rest of the assembly took place in an animated atmosphere, with expressions of hope that a CORPI leader would be elected in the upcoming AIDESEP elections to replace the current president.

But, before that, they had to choose the best candidate, someone able to win the national federation’s elections. First, two CORPI leaders were nominated: its president (Mamerto Maicua, Awajún) and its vice-president (Jamner Manihuari, Kukama-Kukamiria)—following the rule that a leader cannot nominate themselves but must be proposed by another leader to the assembly.19 Next, the election committee was set up: an Awajún leader is appointed as the president of the electoral committee, with a Kukama-Kukamiria leader serving as secretary. They were responsible for ensuring compliance with the rules, overseeing the vote count, and announcing the results. At the end of the vote, the vice-president of CORPI and underdog won with twenty-three ballots, while the Awajún president received only nine votes.

At the end of the assembly the electoral committee reminded the leaders that CORPI’s candidate would have strong chances to win: “We are very well seen by the eight regions. We must support the candidacy of our friend so that he can win.” In fact, CORPI’s leadership had experienced remarkable support from other AIDESEP bases. Alberto Pizango himself, the incumbent president, who had previously won as CORPI’s candidate in 2006, had been re-elected prior to seeking a third term in 2011. But this also means that the current president of AIDESEP was already originating from CORPI. If the AIDESEP bases aimed for alternation, there’s a good chance they would favor a candidate from a different region this time.

However, CORPI remains committed to addressing the issue of disconnection between the regional and national levels, paradoxically underscored by the visit of an AIDESEP representative, which made the political maneuverings of the national leadership palpable. How then, according to regional leaders, should a national leader act? “I would like you, if you have the chance to be elected, not to become like those of ONDEPIP [Organización Nacional de Defensa y Desarrollo de Pueblos Indígenas del Perú, an indigenous organization notorious for its collusion with oil companies]. We want you to be a leader who has vision, who leads his people,” says the president of the Pastaza Quechua federation. An Awajún leader from another local federation, confirms: “As a leader, you have to take a stand, not turn your back, we wouldn’t want that.” We can hear in these remarks the leaders’ ambiguous feelings towards AIDESEP—suspecting a lack of loyalty to their bases, manifested in what they perceive as venality, particularly towards the mining and oil industries.20

Gil Inoach, who had been president of both CORPI and AIDESEP, warns the new candidate about several pitfalls, both in the pursuit of the AIDESEP presidency and in managing the federation if elected:

What AIDESEP must do is unite with its people and continue defending what it has failed to defend. It must be careful, particularly in the choice of its advisors. Because now many of them are with the government. If you’re not careful, they’ll tie your hands and they’ll make sure you don’t speak out against the government. […] We’ll need to reach out to all the regions… But for that, you have to come up with a work plan. When you have a clear idea, that’s when they [the other regional federations] will support you. We don’t want you to settle for secretary of AIDESEP when you could become its president. Here the people have chosen you to be president of AIDESEP, and that’s the way it has to be. Without getting angry with others. Don’t be the kind of leader who, when criticized, pushes people aside, because you might end up surrounded only by leftists, and you’ll get rained on by those.

Inoach speaks from experience. He begins with a critique of the current management: it does not primarily defend the interests of indigenous peoples, but is committed to the cause of the government, which it cannot freely oppose. At the end, he makes a second criticism, against a second type of influence: no longer that of pro-government advisors, but of “leftists,” in other words, peddlers of an ideology of confrontation with the government. On the one hand, there are the institutional entanglements that prevent strong opposition to the government, and on the other, there is the leftist rhetoric that gives the impression of systematic opposition to the state—and both are damaging the indigenous movement. Gil Inoach shows how AIDESEP has become paralyzed in its action and in its thinking. The cause of indigenous peoples is not dictated by ideology, but by commonly-decided goals, primarily territorial autonomy, and this requires a pragmatic approach and the will to resist ideological and institutional influences.

In between these two condemnations, he conveys confidence in CORPI’s candidate’s capability to secure victory in the elections. But this confidence is contingent upon four specified conditions: that CORPI’s candidate is supported by all the components of the federation; that he makes dialogue with the other regions a priority; and that he offers them “a work plan” and “a clear idea.” In other words, a successful campaign for the presidency of AIDESEP should reflect the unity and coherence of the regional federation that acts as its foundation—which entails embodying a clear vision, a comprehensive work plan, and a commitment to open dialogue. This is the task of the assembly: reconciling differences, turning continual divisions into transient unity, and empowering its members and leaders to collectively declare, “we, the Awajún,” “we, the Pastaza Quechua,” and ultimately, “we, the indigenous people.”

Therefore, successful articulation between the regional and national scales of the indigenous organization is to first ensure that the proposed leadership at AIDESEP is already present, at least virtually, at CORPI. Yet, in 2011, CORPI was itself plagued by internal divisions, and the failure of Jamner Manihuari’s candidacy for AIDESEP’s presidency in 2011 was a reflection of CORPI’s failure to offer a sustainable and coherent leadership to its own constituency.

CORPI and its Bases: Electing a President

When, during the November 2011 assembly, a candidate had to be chosen to represent CORPI in the national federation, the Kukama-Kukamiria candidate, with twenty-three votes, received more than double the number of votes compared to his only opponent: his victory partly reflected a rejection of his opponent, the incumbent president of CORPI at that time. Anticipating this rejection, some leaders attempted to propose an open vote as a means to prevent potential disloyalty among voters. But one group insisted on a secret ballot: “We’ve always done it that way! We set up a table, write on a little paper and put it in a box.” Finally, it was agreed that the vote would be secret. However, the attempt to change the voting method indicates internal tensions within CORPI, revealing unspoken and shifting loyalties among the bases.

A year later, these tensions erupted at CORPI’s general assembly in November 2012, during which the election of the new executive board took place. During 2012, that is, in the period between the two general assemblies of CORPI, a group of leaders was preparing for a change of leadership. The driving force behind this movement were CORPI treasurer Juan Tapayuri and vice president Jamner Manihuari, both from the Kukama-Kukamiria group. Backing them was the support of the Shiwilu of Jeberos and the Shawi of Balsapuerto, in the Alto Amazonas province. Jamner Manihuari’s victory in clinching the CORPI candidacy for the presidency of AIDESEP infused hope into this faction, and it was Juan Tapayuri who was nominated to try his luck at being elected president of CORPI in the 2012 assembly.

When, a month before this assembly, I visited the soon-to-be candidate in CORPI’s new offices in Yurimaguas (Alto Amazonas, Loreto), he was working on the federation’s accounting report. Juan Tapayuri complained that morning that he had to do it alone when it should be a team effort. He asserts that he is the one who puts in the most effort at CORPI, diligently preparing reports and handling the majority of administrative tasks to ensure CORPI remains transparent and accountable to its partners, especially to donors who otherwise, as has happened in the past, would not renew their funding. Juan presents himself as the one who takes things in hand, who does not run away from his responsibilities. He is contemplating running in the upcoming election, with the support of several influential leaders. His vision for CORPI is centered on successful alliances with non-governmental partners. Juan Tapayuri thus appears to be a manager and, to some extent, a diplomat, and this is both his value and his weakness as a candidate to lead CORPI. As observed in the 2011 assembly, the leaders prioritize a leader’s ability to firmly confront external entities perceived as threatening, particularly in this region where, as we’ve seen, a form of hostility or antagonistic stance shapes the style of indigenous politics. Furthermore, Juan Tapayuri emerged from the national indigenous organization Confederación de Nacionalidades Amazónicas del Perú (CONAP),21 whose stance towards the private sector is deemed overly accommodating by the leaders of its rival, AIDESEP (to which CORPI is affiliated).

With these image handicaps, Tapayuri’s challenge will be to win the election against the announced Awajún candidate: Marcial Mudarra. Unlike the situation in the 2011 assembly, the current scenario doesn’t revolve around confronting an unpopular leader and relying on a wave of rejection against him. On the contrary, Marcial Mudarra had been elected president of CORPI shortly before the events of Bagua in 2009, and, involved in the revolt, he decided to step down and allow the bases to select someone else in his place. In 2012, this grants him a dual legitimacy: that of the Baguazo activist who is beyond suspicion of collusion with the enemy, and that of the honest leader who prioritizes the interests of his people over personal ambitions for power. There is also a corollary: Marcial Mudarra appears as the one who, having received the anointment of the bases in 2009, was prevented from serving his mandate. His candidacy is viewed by some as an opportunity to right this wrong.

The rivalry between Juan Tapayuri and Marcial Mudarra also reproduces a geographical division within CORPI. The federation represents the populations of two border provinces in the department of Loreto: Datem del Marañón, where the majority are Aénts Chicham, and Alto Amazonas, where the Aénts Chicham are a minority. So, what can the leaders of Alto Amazonas, led by Juan Tapayuri, do to get their candidate elected? Without a strategy of alliance with the bases of Datem del Marañón, Juan’s election seems unlikely. Each federation is entitled to two votes; if we consider the twenty-seven federations allowed to vote in 2011,22 Alto Amazonas has twenty voters and Datem del Marañón has thirty-four: the gap is significant, even when considering a portion of voters who may not adhere strictly to provincial loyalties.

When it was time to nominate candidates for the presidency of CORPI, the Shiwilu leader from Alto Amazonas proposed Juan Tapayuri. The other two candidates proposed for CORPI’s presidency were Aurelio Chino (Quechua from the Pastaza), by his colleague from FEDIQUEP, and, as expected, Marcial Mudarra (Awajún), by another Awajún leader. At the end of the vote, Marcial Mudarra received thirty-one votes, against only fourteen for Juan Tapayuri and five for Aurelio Chino.

As soon as the results were announced, Juan Tapayuri’s key supports protested by leaving the assembly, expressing their strong disagreement with the predominance of Awajún leaders in CORPI. A Shawi leader from Alto Amazonas stood up angrily and walked out of the room, followed a few minutes later by the Shiwilu leader who had proposed Tapayuri’s candidacy. CORPI is politically rooted in San Lorenzo, where the influence of the Aénts Chicham holds sway, both in terms of numerical representation and leadership model.23 These leaders from Alto Amazonas were unwilling to accept this reality any longer. As for Jamner Manihuari, although he comes from the same community and local federation as the unsuccessful candidate Juan Tapayuri, he accepted the outcome of the vote and maintained a low profile throughout the meeting.

Juan Tapayuri and his supporters decided to leave CORPI institutionally, arguing that its leadership only secondarily represented their bases. They created their own regional federation: the Regional Organization for the Development and Defense of the Indigenous Peoples of the Province of Alto Amazonas (ORDEPIAA),24 which is not affiliated with AIDESEP, like CORPI, but with CONAP—AIDESEP’s national competitor, as we have noted. But most of the CORPI bases in the Alto Amazonas province remained loyal to their initial organization. A Kukama-Kukamiria was elected treasurer of CORPI. As for Jamner Manihuari, there never seemed to be any indication of him considering secession. His path eventually led him to assume the presidency of CORPI in 2018—which is another story, beyond the scope of this article. However, we can see that CORPI’s leadership responds neither to a dynamic of alternation nor to a logic of exclusion, but is guided by opportunistic alliances, which are historically dominated by the Aénts Chicham of Datem del Marañón.

Conclusion

In both assemblies examined, albeit through different approaches, the challenge was to identify one or more individuals capable of representing all the facets of CORPI as a multi-ethnic and multi-level organization, thereby advancing the scope of political representation beyond the local assemblies: it’s not necessarily a Shawi individual who will represent the Shawi people, or a Kukama-Kukamiria who will represent their province. Instead, a member of one of the eight ethnic groups CORPI represents will assume leadership over all others, as well as over the two provinces of Datem del Marañón and Alto Amazonas.

The key matter during this transition from one organizational level to another is the cohesion of the indigenous movement facilitated by the deliberations and actions taken during the assemblies. In CORPI, this is evident in how assemblies connect the regional and national levels, such as when nominating its candidate for the presidency of the national federation in 2011. Additionally, CORPI’s assemblies also connects the regional and local levels, as seen in the election of the new executive board by local leaders in 2012. But this article has shown how the endeavor to achieve unity is fraught with conflicts and divisions that can undermine cohesion—so much so that, looking only at the electoral process during the assemblies, the federative system seems to fail at fully establishing the legitimacy of its leaders.

This also explains why indigenous leaders, at all levels, become the subject of rumors and persistent criticism. Their representativeness, despite being institutionally necessary, is generally viewed as fictional. Once again, the assembly holds the position of the “supreme authority,” as it serves as the primary arena for debate, contestation, and the source of the indigenous political discourse. It is also where a collective will is initially manifested and institutionally legitimized. Political representation seems at the antipodes of the assembly’s political practice, which establishes an authority that is only acknowledged in its susceptibility to being challenged. The perpetual tension between the legitimacy of the assembly and the perceived illegitimacy of the elected leaders shapes indigenous politics in the Peruvian Amazon.

In a context dominated by the Aénts Chicham ethnic group, this display of hostility, as analyzed, illustrates how the warlike antagonisms that historically structured intertribal relationships in the region are not being neutralized by politics but rather reshaped by it. Particularly, the predatory stance of the Awajún leaders finds a new space for affirming a warrior ethos in the political arena that emphasizes vision, strength, dominance, and individual prowess (cf. Taylor 2006; 2007). These values are now being mobilized for a political cause that promotes collective action and a common agenda, progressively reorienting the war-like values of confrontation and individualism to nurture a sense of togetherness.

Author

Thomas Mouriès is a French-Peruvian anthropologist. He holds a Ph. D. in Social and Cultural Anthropology from the EHESS in Paris, and is affiliated to the Laboratoire d’anthropologie sociale (CNRS, EHESS, Collège de France). His research focuses on indigenous politics, particularly in the Peruvian Amazon.

thomas.mouries@gmail.com

Laboratoire d’anthropologie sociale (CNRS, EHESS, Collège de France)